What Is a Letter of Interest for Grants?

A letter of interest for grants, also called a letter of inquiry, is a brief introductory document that organizations send to foundations before submitting a full grant proposal. Think of it as a compelling preview that helps funders quickly determine whether your project aligns with their funding priorities.

Key characteristics of grant letters of interest:

Length: One to three pages, typically 1.5-2 pages is ideal. Foundations and other types of funders review dozens of LOIs, so conciseness matters.

Purpose: To secure an invitation to submit a full grant proposal by demonstrating mission alignment and project viability.

Format: Professional business letter with standard components including letterhead, date, salutation, body paragraphs, and signature. This is often attached to an email, snail-mailed, or pasted into a ‘contact us’ form on the foundation’s website.

Timeline: Most foundations and other types of funders respond within 6-12 weeks, though some may take longer depending on their board meeting schedule.

Success rate: Approximately 20-40% of LOIs result in invitations to submit full proposals, though this varies significantly by foundation and program type. For example, the M.J. Murdoch Charitable Trust only invites about 10% of applicants to move forward to the grant application process.

Why Do Foundations Require Letters of Interest?

Understanding why foundations use the LOI process helps you craft more effective letters. The two-stage application process serves important purposes for both foundations and grant seekers.

For Foundations: Program officers may receive hundreds of funding requests annually. Letters of interest allow them to efficiently screen projects, focusing staff time on proposals that genuinely match their mission, geographic focus, and funding capacity. This process also helps foundations manage applicant expectations and reduce the number of declined full proposals.

For nonprofit organizations: The LOI process is designed to save you significant time and resources. Writing a full grant proposal requires hours of staff time. By submitting a brief letter first, you learn whether a foundation is interested before investing in a comprehensive application, which allows you to focus your grant writing efforts on the most promising opportunities. However, in reality, it actually creates more work in most cases, and the turnaround time between the letter of interest results and the full proposal deadline can be astonishingly short.

Industry trend: While there is no authoritative source on the percentage of foundations that require a letter of interest, it’s definitely an essential skill for development professionals and grant writers. In my 25+ years of experience in grant writing, I would estimate that at least 30% of foundations and corporations require one. Government sources also often require a letter of intent, but it is typically a very short survey to help plan for having a sufficient review team in place.

Letter of Interest vs Letter of Intent: What's the Difference?

While the terms sound similar, letters of interest and letters of intent serve different purposes in the funding world.

Letter of Interest (LOI): An exploratory document sent to gauge a foundation's interest in your project. You're asking permission to apply. The foundation has made no commitment, and you haven't been invited yet. This is typically the first contact in the grant relationship.

Letter of Intent: A more formal document indicating a serious commitment to move forward. Often used when a foundation has already expressed interest or when applying to government grants with pre-application requirements. This signals you definitely plan to submit a full proposal.

In grant seeking: Most foundations that use a two-stage process specifically request a "letter of interest" or "letter of inquiry." Always use the exact terminology the foundation uses in its guidelines.

How Long Should a Grant Letter of Interest Be?

Standard length: One to three pages, with 1.5 to 2 pages being the sweet spot for most foundations.

Why this length matters: Foundation staff often review 50-100 LOIs per funding cycle. A concise, well-organized letter respects their time while providing enough detail to make an informed decision.

When to write more: Only exceed two pages if the foundation's guidelines specifically request additional information or if you're describing a complex, multi-year program with significant budget components.

When to write less: Some foundations explicitly state "one-page maximum" in their guidelines. Always follow stated requirements precisely.

Word count guidance: Aim for 800-1,200 words. This allows you to cover all essential components without overwhelming the reader.

The density principle: Every sentence should serve a purpose. If you're struggling to fit everything in two pages, you're likely including unnecessary details. Focus on the most compelling data, the clearest program description, and the strongest alignment statements.

Essential Components: What to Include in a Grant Letter of Interest

Every effective grant LOI follows a proven structure that makes it easy for foundation staff to find key information. Here are the seven essential components in order.

1. Professional Header with Contact Information

Begin your letter with complete organizational details and recipient information formatted as a professional business letter. Remember, forgetting to include your contact information can be detrimental.

Your organization's information should include:

The date: Use the full date format (January 15, 2025) rather than a numerical format.

Recipient's information should include:

Program officer or foundation director's full name with appropriate title (Mr., Ms., Dr.). You can find this in the 990 tax return for the foundation.

Foundation's complete legal name. Refrain from shortening it or using the ‘street name’; foundations tend to be sticklers for the correct use of their name.

Complete street address

City, state, and ZIP code

The salutation: Always address a specific person by name. "Dear Program Officer:" or "To Whom It May Concern:" signals insufficient research. If no contact person is listed, call the foundation office to ask who should receive LOIs. You can also use the 990 Tax Return of the foundation and direct it to the board or trustee president. The salutation is always followed by a colon, not a comma.

Example format:

Westside Link

555 Westside Highway

Anytown, ST 77777

January 15, 2025

Ms. Sarah Chen

Program Director, Community Grants

Heddington Foundation

767 Heddington Street

Heddington, MD 65656

Dear Ms. Chen:

2. Opening Paragraph: Mission, Request, and Alignment

Your opening paragraph is the most critical section of your entire letter. Foundation staff often decide whether to continue reading based solely on these first 3-4 sentences. This paragraph must accomplish three specific goals.

State your mission clearly: Begin with a concise, compelling one-sentence mission statement that immediately conveys your organization's purpose and the community you serve.

Make your specific request: Clearly state that you are requesting permission to submit a full grant proposal. Include the exact dollar amount and the specific program name. Precision matters here. Avoid writing "approximately $20,000" when you mean exactly $20,000.

Demonstrate mission alignment: Show how your program directly connects to the foundation's stated funding priorities. Use language from their website or recent grants when appropriate, but avoid simply parroting their mission statement.

Example opening paragraph: "Westside Link's mission is to foster stability and self-sufficiency for the city's children and their families through programs that feed, clothe, and educate. We are writing to respectfully request permission to submit a grant proposal for $20,000 for our Breaktime-Mealtime program, which enables students to access nutritious meals during school breaks when they would otherwise go without the free and reduced meals they receive during the school year. This program directly aligns with the Heddington Foundation's priority of strengthening lives by supporting human service organizations that provide essential resources to community residents."

What this opening accomplishes: In four sentences, the reader knows who you are, what you want, what you'll do with the funds, and why it matters to their foundation. They can make an initial assessment immediately.

3. Organizational Background and Credibility

This brief section establishes your legitimacy and track record. Foundation staff need confidence that you have the capacity to deliver on your promises.

What to include:

Founding date and brief history: Demonstrates organizational stability and community roots

Core programs and service areas: Shows breadth of expertise and infrastructure

Geographic service area: Confirms you serve the foundation's target region

Notable achievements or recognition: Builds credibility without bragging

Key partnerships: Indicates collaborative capacity and community trust

What to exclude:

Lengthy historical narratives

Lists of every program you've ever offered

Board member names (unless specifically requested)

Detailed organizational structure

Your 501(c)(3) determination date (include this in attachments if requested)

Empowering language approach: Remember to frame your organization as the supporting actor. Your program participants are the heroes of their own stories.

Example paragraph: "Westside Link was founded in 1911 by community members committed to strengthening neighborhood support systems and building resilience among families. By providing access to children's basic resources, students can focus on their education and build pathways to economic stability. Our program areas include nutrition access, educational support, basic needs assistance, and emergency services. We serve 15 neighborhoods across the city's west side, partnering with 12 elementary schools and reaching more than 3,000 families annually."

Length guideline: Keep this section to 3-5 sentences or one short paragraph. Your organizational background is important, but it's not the star of your letter—your program is.

4. The Community Insight Statement: Demonstrating Need

This section makes your case by clearly articulating why your program is necessary. Strong problem statements balance concrete data with humanizing context, showing both the scope of need and the real impact on people's lives.

Components of an effective problem statement:

Lead with your strongest statistic: Open with the most compelling number that demonstrates urgency or scale. This could be a trend showing rapid growth, a percentage revealing widespread impact, or a comparison highlighting disparities.

Use local, specific data: National statistics provide context, but local data proves immediate community need. Partner with school districts, health departments, city agencies, or university researchers to access community-specific information.

Show trends over time: Static numbers are less compelling than trends. Demonstrate that the problem is growing, persistent, or newly emerging. Percentage increases signal urgency better than raw numbers alone.

Break down data by location or demographic: Showing variation helps foundations understand where impact will be greatest. School-by-school, neighborhood-by-neighborhood, or demographic breakdowns make need tangible.

Include humanizing elements: Brief quotes from program participants or community members put faces to statistics without being manipulative. One or two powerful quotes are more effective than many.

Connect to broader context: Briefly mention how local need relates to regional or national trends when relevant. This shows you understand the bigger picture while staying focused on local impact.

Example from the Westside Link letter:

The problem statement effectively uses enrollment data showing a 39% increase in students qualifying for free and reduced meals over four years (from 2,958 to 4,114 students). It then provides school-specific percentages demonstrating that three elementary schools have more than 50% of students needing meal support, with Lake Hills Elementary at 69%. The inclusion of authentic parent quotes—"I'm leaving empty food cartons and packages in the refrigerator and our cupboards, so our children won't realize how bad things are"—humanizes the statistics without sensationalizing.

Common mistakes to avoid:

Using only emotional appeals without data

Citing only national statistics without local context

Overwhelming readers with too many numbers

Making claims without citations

Using outdated data (older than 2-3 years)

Focusing solely on what's wrong rather than what's possible

Empowering language in problem statements: Describe the situation accurately while maintaining dignity. Write about "students who would benefit from nutrition support" rather than "needy children," and "families working to increase food security" rather than "families in crisis."

5. Program Description: Your Solution

After establishing need, describe exactly what you will do to address it. Specificity builds confidence—vague descriptions suggest unclear planning.

Essential details to include:

Specific activities: What services will participants access? What exactly happens in your program? Describe the tangible activities, not just conceptual approaches.

Timeline and frequency: When do activities occur? How often? For how long? Is this a one-time event, ongoing service, or time-limited intervention?

Target population: Who will benefit? How many people? What are their characteristics? Be specific about both who is included and who is served.

Delivery method: How do services reach participants? Do they come to you, do you go to them, or is it a hybrid model?

Quality assurance: Who ensures quality and effectiveness? Mention professional credentials, training, or review processes that demonstrate competence.

Participant agency: Use language that centers participants as active agents. Rather than "we will provide meals to children," write "students will access nutritious meals through our program."

Example from Westside Link:

The program description clearly explains that students access meal boxes during three school breaks: spring break and mid-winter break (each one week) and winter break (two weeks). Each box contains breakfast, lunch, and a snack for five days, totaling ten meals plus snacks and a grocery voucher for perishable items. Boxes are available for all children in participating families. Volunteers pack boxes under the guidance of a nutritionist who reviews the contents for nutritional adequacy.

What makes this effective: A reader unfamiliar with the program could now explain how it works. The description includes specific details (what's in a box, which breaks are covered, who reviews quality) without getting bogged down in operational minutiae.

Length guideline: 1-2 paragraphs or 4-8 sentences. Provide enough detail for clarity without overwhelming the reader with procedures.

6. Goals and Measurable Objectives

Foundations invest in results, not just activities. This section demonstrates that you've thought strategically about how you'll measure success and create meaningful change.

The difference between goals and objectives:

Your goal is the overarching change you seek to accomplish—a broad statement of desired impact. Goals describe the ultimate outcome you're working toward.

Your objectives are specific, measurable activities or milestones that support achieving your goal. These are concrete, time-bound, and quantifiable.

Writing SMART objectives:

Every objective should meet five criteria:

Specific: Clearly defined activities or outcomes, not vague intentions. "Host informational sessions" is specific; "raise awareness" is not.

Measurable: Include numbers, percentages, or other quantifiable metrics. How will you know if you achieved this objective?

Achievable: Realistic given your resources, timeline, and organizational capacity. Avoid objectives that depend entirely on factors outside your control.

Relevant: Directly connected to your stated goal and program activities. Every objective should clearly contribute to your desired impact.

Time-bound: Include a timeframe for completion, whether explicit ("by June 2026") or implied by the grant period.

Example from Westside Link:

Goal: Reduce food insecurity for children and positively impact their ability to learn in school by ensuring students can access nutritious meals during school breaks.

Objectives:

Host at least ten informational sessions about the program throughout the school district, with targeted outreach to schools where enrollment in free and reduced meal programs exceeds 50%

Maintain or increase the number of students accessing the program to at least 1,600 participants

Receive positive feedback indicating that at least 70% of key stakeholders (school staff, volunteers, and participating families) rate the program as 'satisfied' or 'very satisfied' via annual surveys.

Why these work: Each objective includes specific numbers (10 sessions, 1,600 students, 70% satisfaction), uses measurable language ("host," "maintain," "receive"), and connects directly to the stated goal. Success can be clearly evaluated.

How many objectives: Include 2-4 objectives. Fewer than two suggests limited planning; more than four becomes difficult to track and may seem unrealistic within typical grant periods.

Common mistakes:

Confusing activities with outcomes (activities are what you do; outcomes are what changes)

Using unmeasurable language ("improve understanding," "increase awareness")

Setting objectives you can't realistically evaluate

Making objectives too complex or dependent on external factors

7. Budget Overview and Funding Strategy

Foundations want to understand both how you'll use their grant and how your program fits into a larger funding ecosystem. This section demonstrates financial competence and sustainability.

Essential budget information:

Total program cost: State the full cost to operate this program annually. This provides context for your request.

Cost per unit: Break down expenses to per-person, per-meal, or per-service cost. This demonstrates efficiency and helps foundations compare your approach to similar programs.

Your specific request: Clarify exactly what the requested grant will fund. Will it cover specific activities, a portion of the program, or particular budget lines?

Other confirmed funding sources: List other grants, donations, or revenue supporting this program. Include foundation names and amounts when possible. This demonstrates diversified support and reduces foundation risk.

Funding gap: Explain how you'll secure the remaining needed funds if applicable. Mention upcoming fundraising events, pending grant applications, or earned revenue strategies.

Organizational budget context: Include your total organizational budget for the current year. This helps foundations assess your capacity and understand the program's scale relative to your organization.

Future sustainability: If relevant, briefly mention your sustainability strategy. Will this program eventually generate earned income, build an endowment, or secure ongoing public funding?

Example from Westside Link:

"Our Breaktime-Mealtime program budget is $90,000 annually. Since dedicated volunteers pack and distribute boxes, this budget consists primarily of food and supplies. This breaks down to $22,500 for each of the four weeks of school breaks, enabling approximately 1,600 students to access breakfast, lunch, and snacks for five days at a cost of $2.80 per child per day. As the program grows, we plan to raise additional funding to hire a part-time program coordinator to strengthen outreach efforts, volunteer coordination, and program evaluation.

Other funding sources supporting this program include grants from the Norcliffe Foundation ($20,000), Trevor Foundation ($10,000), and Rotary Club ($3,000). We will raise the remaining funds through our annual Gala, individual donations, and additional grant applications. Our total organizational budget is $1,017,938, demonstrating our capacity to manage this program as part of our broader mission to support children and families building economic stability."

Why this works: The reader understands the full program cost, sees the cost efficiency ($2.80 per child per day), knows how the requested $20,000 fits into the funding picture, and has confidence that the organization can manage these funds appropriately within their larger budget.

What to avoid:

Providing excessive budget detail (save this for the full proposal)

Listing only your organization's need without showing other support

Hiding or obscuring your total program cost

Making the request seem like your only funding source

Failing to explain how funds will be used

8. Closing Paragraph: Gratitude and Call to Action

Your closing should gracefully conclude the letter while reinforcing key themes and inviting next steps.

What to include:

Expression of gratitude: Thank the reader sincerely for considering your request. Acknowledge that foundations review many worthy proposals.

Reiteration of alignment: Briefly reconnect your program to the foundation's mission, reinforcing the partnership opportunity.

Invitation for next steps: Express hope for an invitation to submit a full proposal without being presumptive.

Clear contact information: Provide your direct phone number and email address, making it easy for staff to reach you with questions.

Professional tone: Maintain confidence in your program while remaining respectful and humble about the foundation's decision-making process.

Example closing: "Thank you for considering this request. We hope that our shared commitment to ensuring students have the resources they need to thrive will lead to a partnership between Westside Link and the Hicks Foundation. We would welcome the opportunity to submit a full grant proposal providing additional details about program impact, evaluation methods, and organizational capacity. Please contact me with any questions at (555) 555-5555 or laura@westsidelink.org."

What to avoid:

Presumptive language ("We look forward to receiving your grant" or "When you fund this program")

Overly humble language ("We know you probably have better options" or "This is probably not your priority")

Pressure tactics ("We need an answer quickly" or "Children will suffer without this")

Forgetting contact information

Introducing new information that should have been in earlier sections

How to Format a Grant Letter of Interest

Professional formatting enhances readability and demonstrates attention to detail. Follow these formatting guidelines for maximum impact.

Page length: Aim for 1.5 to 2 pages. Rarely exceed 2.5 pages unless guidelines specify otherwise.

Font selection: Use professional, easy-to-read fonts in 11 or 12-point size. Recommended options include Times New Roman, Arial, Calibri, or Georgia. Avoid decorative, script, or unusual fonts.

Line spacing: Single-space the body of your letter with double spaces between paragraphs. This creates clean visual breaks without wasting space.

Margins: Use standard one-inch margins on all sides. Don't shrink margins to fit more content—this makes text harder to read.

Paragraph structure: Keep paragraphs focused and digestible. Aim for 4-8 sentences per paragraph. Break up long paragraphs into smaller sections.

Organization name and logo: If your letterhead includes your logo, place it at the top. Ensure it's of professional quality and appropriately sized.

Headers and emphasis: Use bold sparingly for subheadings if needed, but avoid excessive formatting. Don't underline, use all caps, or over-bold text.

Page numbers: If your letter extends to a second page, include page numbers and your organization's name in the header or footer.

Signature block: Leave space for a handwritten signature if sending hard copies. Include typed name, title, organization name, phone number, and email below the signature line.

File naming: If submitting electronically, use a clear file name like "WestsideLink_LOI_HicksFoundation_Jan2025.pdf"

Writing Style and Tone for Grant Letters

How you write is as important as what you write. These style principles will strengthen your letter's impact.

Active voice and participant agency: Use active voice, strong verbs, and make program participants the heroes of their own story. "More than 1,600 students will access meals from Westside Link" centers the students' agency rather than positioning them as passive recipients.

Concrete, specific language: Replace vague terms with precise details. Instead of "many children," write "1,600 students." Instead of "some schools," name them specifically or provide exact numbers. Specificity builds credibility.

Empowering, asset-based language: Focus on strengths, goals, and capabilities rather than deficits. Write about "building economic stability" rather than "combating poverty," "families working to increase resources" rather than "needy families," and "students accessing nutrition support" rather than "hungry children." This approach maintains dignity while clearly communicating need.

Professional but warm tone: Strike a balance between formal professionalism and genuine passion for your mission. Your letter should sound like a competent professional who deeply cares about this work, not a bureaucrat filling out forms.

Data-driven with human context: The strongest letters integrate compelling statistics with humanizing stories. Data proves scope; stories make it personal and memorable.

Clear, jargon-free writing: Avoid nonprofit jargon, acronyms without explanation, and overly technical language. Write clearly enough that someone outside your field can understand your program.

Confident without arrogance: Express confidence in your organization's capacity and your program's potential without suggesting you're the only solution or making guarantees about outcomes beyond your control.

Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing Grant LOIs

Learning from common pitfalls helps you craft stronger letters. Avoid these frequent mistakes.

Writing too much: Foundation staff review dozens of LOIs. A letter exceeding three pages signals you can't synthesize information effectively or respect their time.

Failing to research the foundation: Generic letters that could be sent to any foundation demonstrate laziness. Customize each letter to show you understand their priorities, recent grants, and specific focus areas.

Burying the request: Don't make readers hunt for what you want. State your specific dollar amount and program name clearly in the opening paragraph.

Weak or missing mission alignment: Never assume alignment is obvious. Explicitly connect your program to the foundation's stated priorities using concrete language.

Using only emotion or only data: Balance is key. Data without stories feels cold; stories without data lack credibility.

Unmeasurable objectives: Avoid vague objectives like "increase awareness" or "improve outcomes." Use specific, quantifiable language: "Distribute 400 resource guides to participating families" or "Achieve 80% improvement in post-program knowledge assessments."

No proofreading: Typos, grammatical errors, and formatting inconsistencies suggest carelessness with your organization's work. Have at least two people review your letter before submission.

Missing deadlines: Submit early when possible. Last-minute submissions are more likely to contain errors and may miss technical cutoffs.

Ignoring guidelines: If a foundation specifies requirements for format, length, attachments, or submission method, follow them exactly. Failure to follow instructions often results in automatic disqualification.

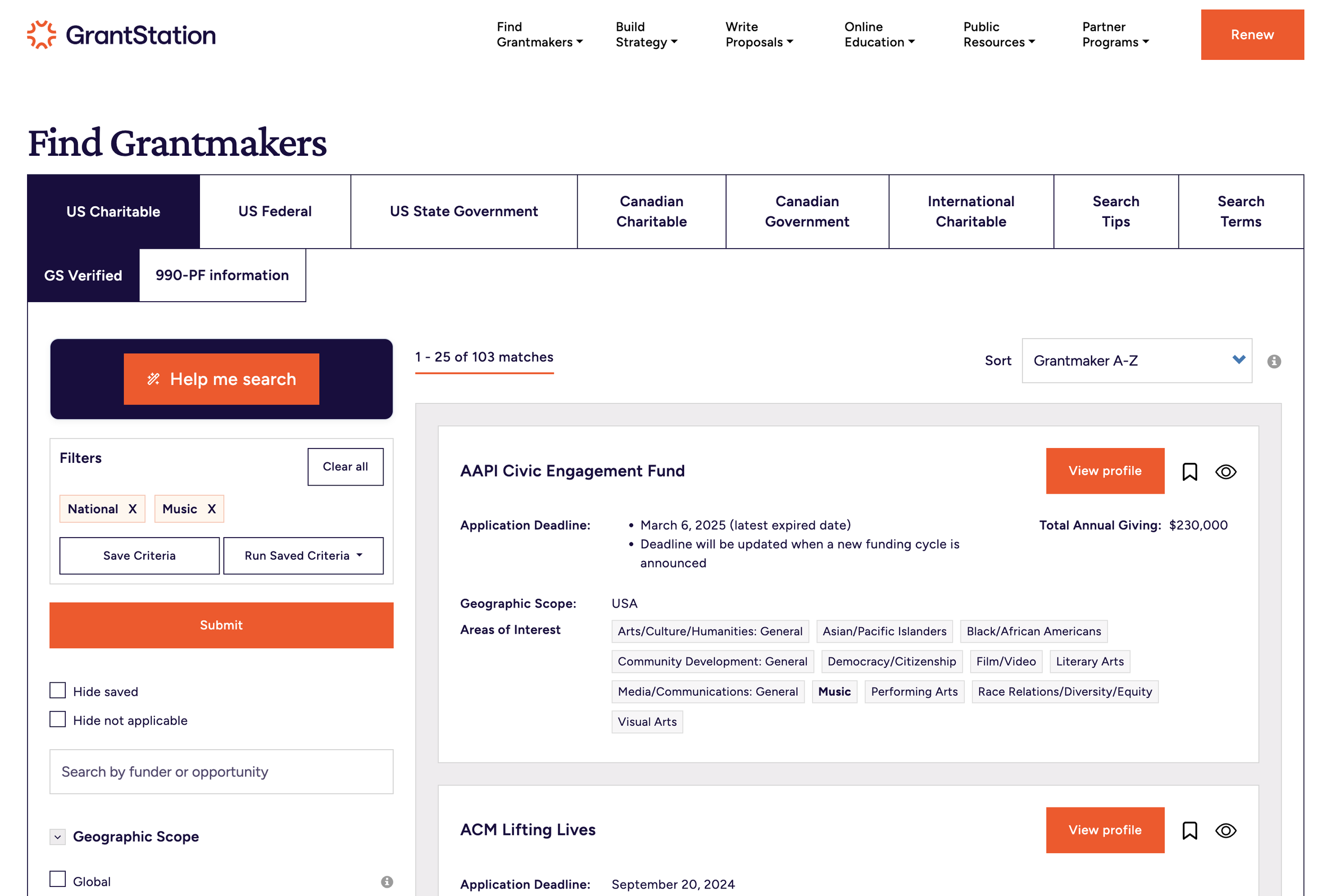

Sending to the wrong foundation: Some organizations waste time applying to foundations whose guidelines explicitly exclude their type of organization, geography, or program area. Read the eligibility criteria carefully before investing time.

Step-by-Step Process: How to Write Your Grant Letter of Interest

Follow this systematic approach to create a compelling letter of interest efficiently.

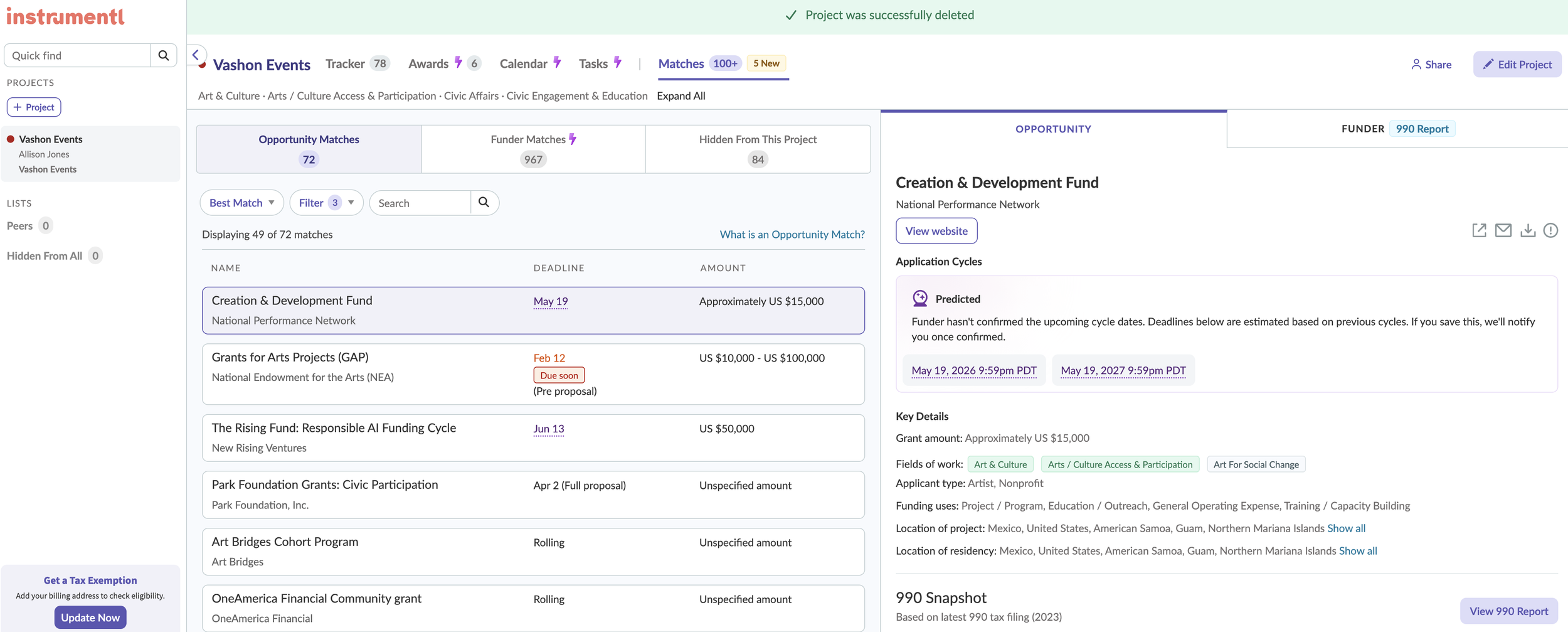

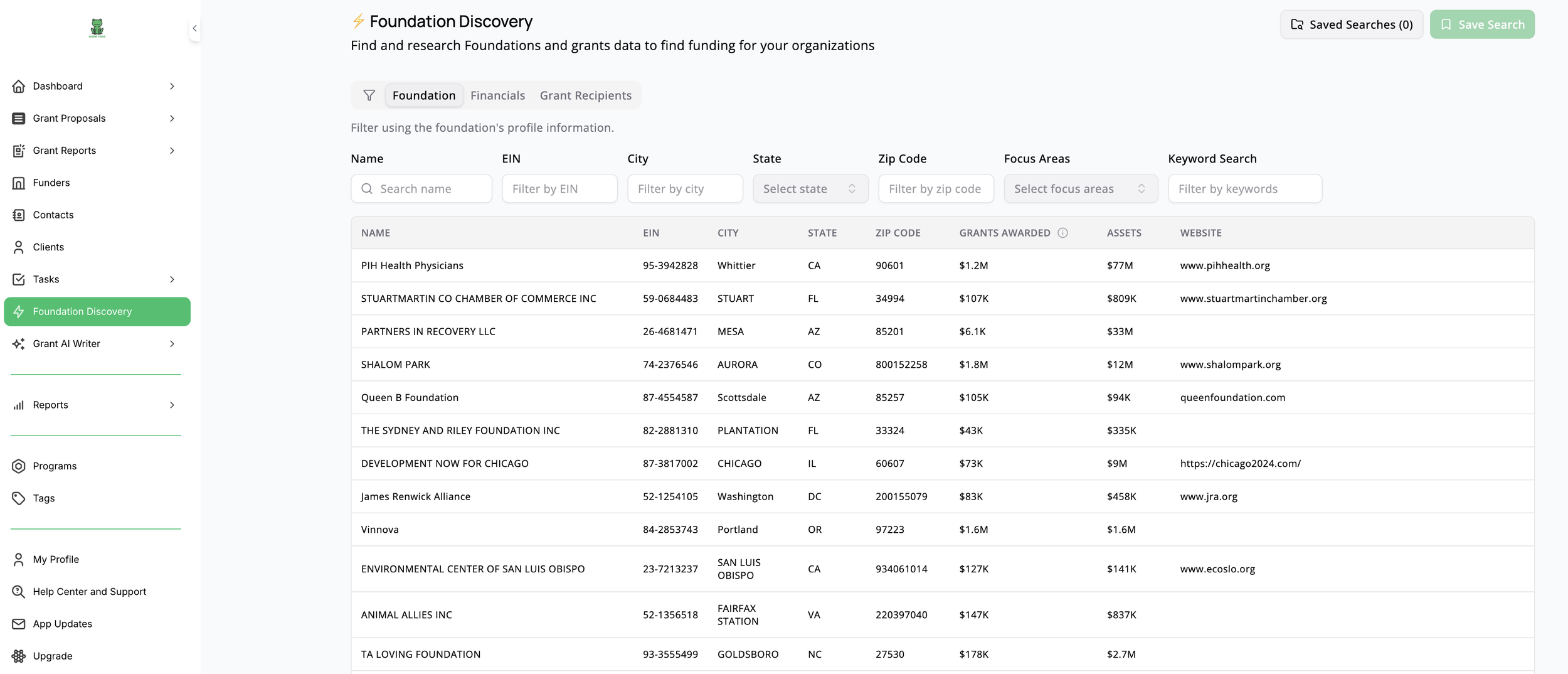

Step 1: Research the foundation thoroughly (1 hour)

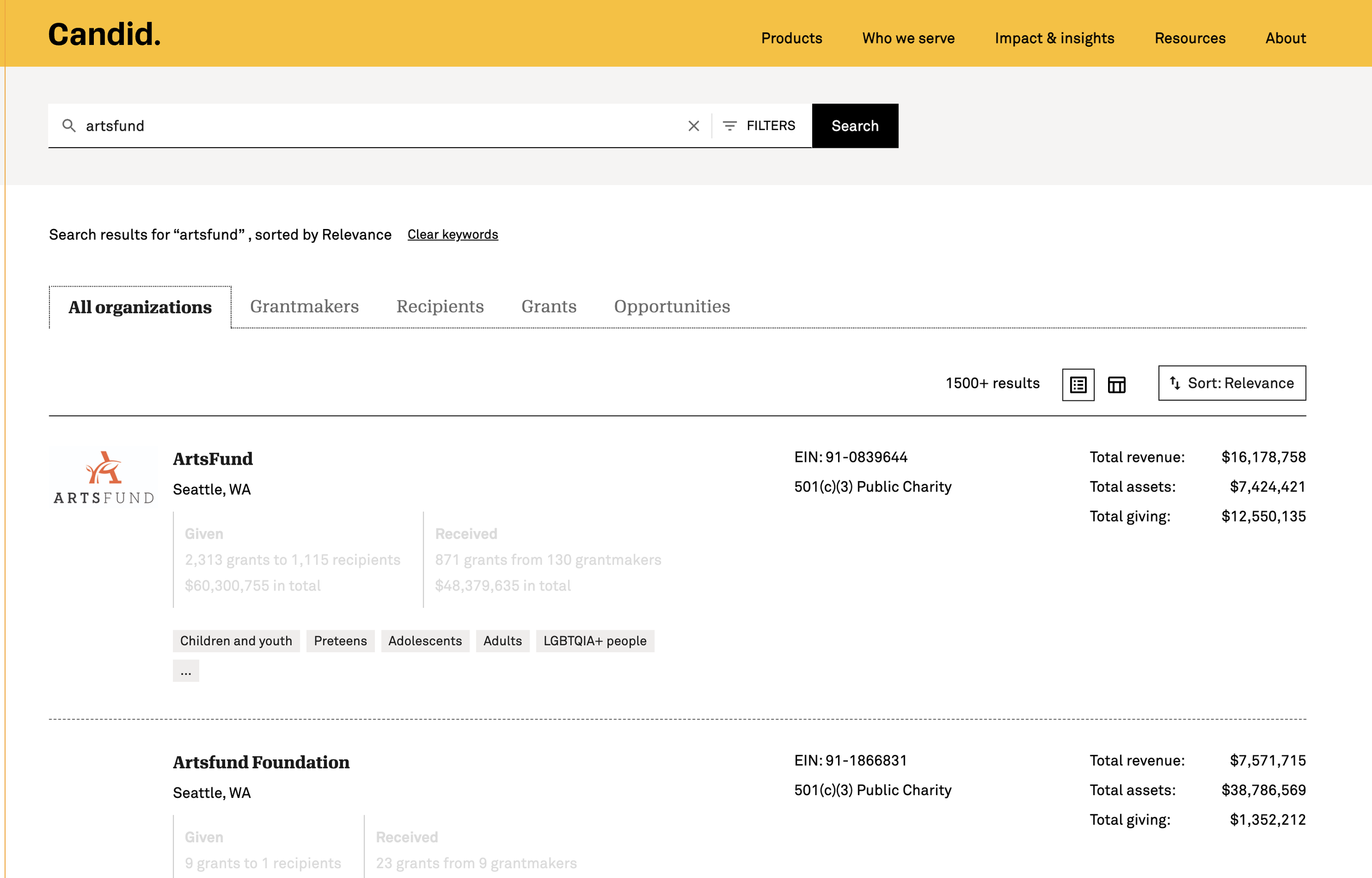

Before writing a single word, invest time in understanding your potential foundation. Review their website, read their mission and values statements, study recent grants (available on their 990 tax form or website), identify program officers and their areas of focus, note application guidelines and deadlines, and understand geographic or program restrictions.

Step 2: Gather your strongest evidence (1 hour)

Collect the data, stories, and information you'll need. Compile recent program statistics and outcomes, gather compelling participant quotes or testimonials, locate relevant community need data, review your program budget and expenses, list other funding sources and amounts, and prepare your organizational budget figure.

Step 3: Create an outline (30 minutes)

Map out your letter's structure before writing. Identify your most compelling opening hook, select your strongest 2-3 pieces of need data, choose which program details are most important, write your 2-4 SMART objectives, and determine your budget message and funding strategy.

Step 4: Write the first draft (1 hour)

Write freely without editing. Focus on getting all essential information down. Start with whichever section feels easiest—you don't have to write in order. Many writers find the opening paragraph easiest to write after completing the body sections.

Step 5: Revise for content and clarity (45 minutes)

Review your draft critically. Ensure every component is present, verify all data is accurate and sourced, check that objectives are SMART and measurable, confirm mission alignment is explicit, and strengthen weak or vague language.

Step 6: Edit for conciseness (45 minutes)

Cut ruthlessly. Remove redundant information, eliminate unnecessary adjectives and adverbs, replace passive voice with active voice, delete entire sentences that don't serve a clear purpose, and condense wherever possible without losing meaning.

Step 7: Format and proofread (45 minutes)

Polish your letter professionally. Apply consistent formatting throughout, check spelling and grammar carefully, verify all names, titles, and organizations are correct, ensure contact information is accurate, and read the letter aloud to catch awkward phrasing.

Step 8: Get feedback (varies)

Have at least two people review your letter: someone familiar with your program and someone unfamiliar with it. The insider checks for accuracy; the outsider checks for clarity.

Step 9: Submit according to guidelines (30 minutes)

Follow submission instructions precisely. Submit via the requested method (online portal, email, or mail), include all requested attachments, meet the deadline with time to spare, and keep a copy for your records.

Total time investment: Approximately 4-5 hours for a strong letter of interest, significantly less than the 20-40 hours required for a full proposal.

What Happens After You Submit Your Letter of Interest?

Understanding the review process helps manage expectations and plan next steps.

Initial screening (1-2 weeks): Foundation staff review all LOIs received during the submission period. They eliminate projects that don't align with funding priorities, fall outside geographic restrictions, or exceed available grant ranges.

Detailed review (1-2 weeks): Promising LOIs receive more thorough evaluation. Staff may research your organization, review your website and recent Form 990, check references or past foundation relationships, and prepare recommendations for decision-makers.

Board or committee review (1-2 weeks): Selected LOIs are presented to the foundation's board of directors or grants committee during their next scheduled meeting. Meeting frequency varies—some boards meet monthly, others quarterly.

Decision notification (3-6 weeks total): You'll receive one of three responses:

Invitation to submit a full proposal: Congratulations! You've passed the first hurdle. You'll receive specific instructions, required components, and a submission deadline (typically 4-8 weeks). This doesn't guarantee funding, but it means you're seriously under consideration.

Decline with feedback: Some foundations provide brief explanations for why your project wasn't selected. This feedback is valuable—use it to strengthen future applications.

Decline without feedback: Many foundations receive far more qualified requests than they can fund. A generic decline letter doesn't reflect poorly on your organization or program—it simply means resources were limited or priorities shifted.

Important perspective: Even excellent programs receive more declines than approvals. Grant seeking requires persistence. A declined LOI might mean:

The foundation received proposals from organizations they've funded previously

Your geographic area or program type wasn't the priority this cycle

The foundation's board shifted focus to emerging issues

Other proposals addressed more urgent needs

Your program timing didn't align with their funding calendar

Don't interpret declines as judgments on your organization's worth or program quality.

Following Up on Your Letter of Interest

Professional follow-up demonstrates respect for the foundation's process while keeping communication lines open.

If invited to submit a full proposal:

Respond immediately with a brief email thanking them for the invitation and confirming you'll submit by the deadline. Note the deadline prominently in your calendar. Consider calling the program officer to ask clarifying questions about their priorities, specific emphasis areas, or required components. Begin working on your full proposal promptly—the timeline will be tight.

If declined:

Send a brief, gracious thank-you note within a week. Express appreciation for their consideration and hope to connect in the future when priorities align. Ask if you may submit an LOI for a different program or in the next funding cycle. Request feedback if they're willing to provide it (but don't pressure if they decline). Update your foundation research database with any information you learned through this process.

If you hear nothing:

Most foundations specify their review timeline in guidelines or confirmation emails. If that period has passed with no response, send a polite inquiry. Keep it brief: "I'm following up on our letter of interest submitted on [date] requesting support for [program name]. Could you provide an update on the review timeline or next steps? Thank you for your consideration."

When not to follow up:

If guidelines explicitly state "do not call or email," respect this boundary. If you received a clear decline letter, additional follow-up (beyond a thank-you note and feedback request) is inappropriate.

Letter of Interest Checklist: Are You Ready to Submit?

Use this checklist to verify your letter includes all essential components and follows best practices. Use the foundation’s specific guidelines. However, if no guidance is provided, use the following format and structure.

Format and Structure:

Letter is 1-3 pages (ideally 1.5-2 pages)

Professional business letter format with complete contact information

Letter addressed to a specific person by name and title

Professional 11-12 point font (Times New Roman, Arial, Calibri, or Georgia)

Single-spaced with double spaces between paragraphs

Standard one-inch margins

Page numbers included if more than one page

File named clearly for electronic submission

Content Components:

Opening paragraph states mission, specific dollar amount requested, program name, and mission alignment

Organizational background establishes credibility in 3-5 sentences

Problem statement includes compelling local data and shows trends

Problem statement includes humanizing context (quotes or brief examples)

Program description explains specific activities, timeline, and target population

Program description uses empowering language centering participant agency

Goal statement articulates desired impact

2-4 SMART objectives that are specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound

Budget overview includes total program cost and cost per unit

Other funding sources listed with amounts

Total organizational budget provided for context

Closing expresses gratitude and invites next steps

Direct contact information provided (phone and email)

Quality and Style:

Foundation's priorities and language reflected throughout

Every claim backed by data or evidence

Active voice used throughout

Empowering, asset-based language

No jargon, acronyms explained, clear language

No typos or grammatical errors

At least two people reviewed the letter

All names, titles, and organizations verified correct

All numbers and statistics verified accurate

Submission follows stated guidelines exactly

Research and Alignment:

Foundation's name, address, and contact person verified correct

Confirmed your organization meets eligibility requirements

Confirmed geographic service area matches foundation's focus

Confirmed program type aligns with foundation's priorities

Referenced specific foundation priorities or recent grants when appropriate

Request amount falls within foundation's typical grant range

Frequently Asked Questions About Grant Letters of Interest

How long does it take to write a letter of interest?

Expect to invest 4-5 hours for a strong letter of interest, including research, writing, revision, and review. This breaks down roughly into 1 hour for foundation research, 30 minutes drafting an outline, 1 hour gathering data and evidence, 45 minutes writing the first draft, 45 minutes revising and editing, and 45 minutes formatting, proofreading, and getting feedback. While this seems significant, it's far less than the 20-40 hours typically required for a full grant proposal.

Can I send the same letter to multiple foundations?

No. Each letter must be customized to the specific foundation's priorities, language, and requirements. While you can use the same core program description and data, you must customize the opening paragraph to demonstrate specific alignment, adjust emphasis based on each foundation's priorities, use language that reflects their mission and values, and ensure all guidelines and requirements are followed precisely. Generic letters are immediately obvious to foundation staff and significantly reduce your chances of success.

What if the foundation doesn't list a specific program officer?

Call the foundation office and ask who should receive letters of interest for your program area. Most staff will gladly provide this information, or you can find it on the 990 Tax Return for the foundation, addressing it to the program officer, president, or secretary. If no one is available or the foundation prefers no direct contact, address your letter to "Board of Trustees." Avoid "To Whom It May Concern."

Should I include attachments with my letter of interest?

Only include attachments if specifically requested in the foundation's guidelines. Most foundations want only the letter at the LOI stage, reserving detailed documents for full proposals. Commonly requested attachments at the LOI stage might include a one-page organizational budget summary or IRS 501(c)(3) determination letter. Never send unrequested attachments—this suggests you can't follow instructions.

How much detail should I include in the budget section?

Provide a high-level overview, not a line-item budget. Include your total program budget, cost per participant or unit of service, your specific funding request and what it will cover, other confirmed funding sources with amounts, and your total organizational budget for context. Save detailed line-item budgets, budget narratives, and financial statements for the full proposal.

What's the success rate for letters of interest?

Success rates vary widely by foundation, program type, and competition level, but generally, 20-40% of LOIs result in invitations to submit full proposals. The important thing to remember is that this is an opportunity to begin building a relationship with the grantmaker, whatever the immediate outcome. Think of this process as a step to open communication channels and get to know the foundation. Often, a longer courting phase results in a larger grant down the road.

Should I follow up if I don't hear back?

Yes, but only after the stated review period has passed. If the foundation indicates they'll respond within 8 weeks, wait at least 9 weeks before following up. Send a brief, professional email asking for a status update. If you receive no response to your follow-up after 2 weeks, you can assume it's a decline and move on.

What if my program doesn't perfectly align with their priorities?

Resist the temptation to apply. Foundation staff can easily identify applications that don't genuinely align with their mission. Instead, invest your time pursuing foundations where alignment is strong and clear. Forcing a connection where none exists wastes everyone's time and may harm your organization's reputation with that foundation. Even more concerning, this practice of submitting misaligned applications is causing more foundations to move to invitation-only processes or stop accepting unsolicited proposals entirely, making funding increasingly difficult to access for all nonprofits.

Can I call a program officer to discuss my idea before submitting?

This depends on the foundation's culture and stated preferences. Some foundations welcome preliminary conversations; others prefer to review written LOIs first. Check the foundation's website or call their general office number to ask about their preference. If they welcome pre-submission calls, prepare thoughtful questions rather than a pitch. Be ready with a brief introduction to your organization (30 seconds to 1 minute), then focus on listening and learning. Ask about their current priorities, upcoming deadlines, or whether your program area aligns with their focus. The goal is to gather information and build a relationship, not to sell your project.

How should I handle if my request amount changes after I submit the LOI?

Avoid changing your request amount if at all possible. Changing the amount after submission signals poor planning and can damage your credibility with the foundation. If you absolutely must adjust the amount due to significant unforeseen circumstances, contact the program officer immediately to discuss the situation before submitting your full proposal. Be prepared to explain clearly why the change is necessary and what has changed since your LOI. Even small adjustments should be discussed with foundation staff rather than simply appearing in your full proposal without explanation. The best approach is to ensure your budget is thoroughly researched and realistic before submitting your initial LOI.

What if I made a mistake in my submitted LOI?

If you notice a minor error (typo, small formatting issue) after submission, don't resubmit or call attention to it. Foundation staff expect occasional small errors and won't reject an otherwise strong proposal for minor mistakes. If you discover a major error (wrong funding amount, incorrect data, missing entire section), contact the foundation immediately, explain the situation professionally, and ask if you may submit a corrected version.

Do I need board approval before submitting a letter of interest?

You need the approval of the executive director, or the board president if it's an all-volunteer organization. Only the official authorized representative of the organization should sign and submit LOIs and grant proposals. The person who signs is legally attesting that all information is true and accurate. Submitting false or misleading information could lead to fraud allegations, loss of tax-exempt status, or disqualification from future funding. Verify all data before submission.

Advanced Tips for Competitive Letters of Interest

Once you've mastered the basics, these advanced strategies can strengthen your letters further.

Lead with your most compelling evidence: Don't bury your strongest data in the middle of paragraphs. Front-load the most impressive statistics, trends, or outcomes in the first sentence of relevant sections.

Use strategic comparison: When appropriate, position your program's efficiency, reach, or outcomes against national benchmarks or similar programs. "At $2.80 per child per day, our program delivers nutrition support at 40% below the national average cost while maintaining high satisfaction ratings."

Demonstrate collaborative capacity: Foundations increasingly value partnerships. Mention formal collaborations with schools, government agencies, or other nonprofits that strengthen your program's reach or effectiveness.

Address obvious questions proactively: If a skeptical reader might question your approach, address it directly. "While some programs provide meal vouchers, our meal box approach ensures nutritional quality while honoring family dignity and choice through included grocery vouchers for perishable items."

Show responsiveness to feedback: If you've previously submitted to this foundation, mention how you've incorporated any feedback or strengthened the program based on their suggestions.

Connect to current priorities: If the foundation recently expressed interest in specific issues (equity, climate, technology integration), thoughtfully connect your program to these themes when genuinely relevant—but never force artificial connections.

Quantify program growth strategically: Showing demand growth (23% increase in participants) signals both community need and organizational capacity to scale effectively.

Include unexpected stakeholder voices: Beyond typical participant quotes, consider brief statements from teachers, volunteers, partner organizations, or community leaders that validate your program's impact.

Download: Free Letter of Interest Template and Checklist

To help you get started, we've created free downloadable resources:

Letter of Interest Template: A fill-in-the-blank template following the structure outlined in this guide, with prompts for each essential component.

LOI Submission Checklist: A printable checklist to ensure you've included all necessary elements before submitting.

Sample Letter of Interest: Download the complete Westside Link sample letter referenced throughout this article to see these principles in action.

These resources provide practical frameworks you can customize for your organization's unique programs and funding needs.